Nathanael Greene was one of the most successful generals in American history. A highly competent tactician, he served in the Continental Army during the entirety of the Revolutionary War and was George Washington's most trusted commander. Greene was born on Aug. 7, 1742, into a Quaker family in Potowomut, Warwick, R.I. His ancestors had helped establish the colony in the 1630s.

He was an excellent student and learned Latin and advanced mathematics; a voracious reader, he later built a private library that included more than 200 books and helped start the first public school in the town where he lived. He found work as a blacksmith, in his father's foundry, Coventry. His father, also named Nathanael, died in 1770. The younger Nathanael got elected to the colonial General Assembly and was re-elected multiple times. He married Catherine Littlefield on July 20, 1774; they would eventually six children. As the likelihood of fighting grew, Greene formed a local militia, near Coventry, where he lived. People of his faith usually chose pacifism, but Greene wanted to fight for his country's freedom and eventually joined the Continental Army. He came to be known as the "Fighting Quaker." Greene walked with a slight limp, which limited his ability to be in the front lines with his fellow militiamen. He turned his keen mind to the study of military tactics and became an expert in the subject. He joined the Rhode Island Army of Observation after the Battles of Lexington and Concord and a few weeks later led his troops into battle during the siege of Boston. Greene was a brigadier general in his local militia, which were known as the Kentish Guards. He obtained the same rank in the Continental Army on June 22, 1775, and, not long afterward, met George Washington in person. The two shared a mutual respect and became close friends. When British troops left Boston in March 1776, Washington named Greene to command the trips there. A bit later, Greene went to New York to take command on Long Island, along with a promotion to major general. Greene was ill with a bad fever when his troops lost the Battle of Long Island. He was in command at the Battle of Harlem Heights and gained command of Continental forces in New Jersey. British successes in the New York area multiplied, as the American defenders lost Fort Washington and then Fort Lee. Greene and Washington both wanted to burn New York rather than let the British gain control of it, but Congress would not approve the move.

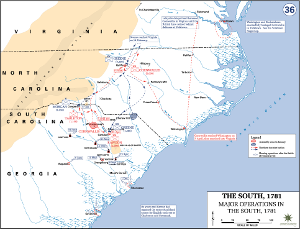

Greene found more success at the Battle of Trenton, leading a wing during the American victory there, and followed that up with another role in the following American victory, at Princeton. However, the losses kept coming, for Washington and Greene. Defeats at Brandywine and Germantown led to the British seizure of Philadelphia, and the Continental Army settled in for a nearly disastrous winter at Valley Forge. Greene was on the battlefield at the Battle of Monmouth, leading the right wing in a struggle that ended inconclusively. Greene willingly accepted Washington's appointment as quartermaster but found his predecessors' frustrations to be his own, as he struggled to find enough supplies to keep the Continental Army fighting fit. He proved to be more than up to the task, however, and was generally lauded for the work that he did this role, which he kept for two years. Greene served for a time as commander of West Point, after the defection of Benedict Arnold. He also presided over the court-martial that resulted in a death sentence for the spy John Andre. In October 1780, Washington named Greene commander of the Continental Army in the South, replacing Gen. Horatio Gates, who had led the Americans into the latest in a series of disasters. In the summer of 1780, the British Army had won a strong victory at the Battle of Camden and seized control of Georgia and the Carolinas. The war in the North had descended into a stalemate by this time, thanks to the entry of France into the war after the pivotal American victory at Saratoga.

Greene arrived in Charlotte, N.C., and brought his customary skill and acumen to the task of reorganizing the southern army. The result was a string of victories such as had not been seen in the north. The Continental Army had already won the Battle of Kings Mountain while Greene was en route; the Americans then won the Battle of Cowpens. Greene made the daring decision to divide his meager forces, and it forced the British commander, Charles Cornwallis, do to the same. Greene gave command of the other half of his army to Daniel Morgan. American forces fought on, employing a mixture of direct attack and misdirection. British armies won battles at Guilford Court House and Hobkirk's Hill, but British losses were so much more that they relied more and more on hunkering down and waiting for reinforcements or, in effect, moving back north. Greene pursued the British commander Charles Cornwallis northward, retaking the captured cities of North Carolina in the process. Greene played a primary role in convincing Cornwallis to keep on retreating until he reached the Yorktown peninsula, where he would ultimately surrender his forces to Washington, effectively ending the war. At the same time, Greene struck at another target, resulting in the Battle of Eutaw Springs. British losses were such that they retreated again, to Charleston. This became the last bastion of British troops in the South and the last to surrender, in 1782. Among the commanders of this liberation campaign were "Mad" Anthony Wayne, who would go on to greater fame in the Northwest, fighting Native Americans, and Francis Marion, the guerrilla leader known as the "Swamp Fox." After the war, with no battles to fight, Greene settled into retirement at Mulberry Grove, his estate, near Savannah, Ga. He had spent a lot of his own money during the war, however, and so he didn't have a lot of personal wealth left; he had even sold his home in Rhode Island to help buy equipment for Continental Army troops. All three of Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina gave him land in appreciation for his wartime efforts. He died of sunstroke on June 19, 1786. He was 44. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White