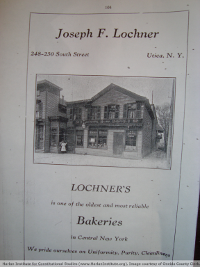

One of the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark decisions was Lochner v. New York, which the court handed down on April 17, 1905. The 5–4 decision was a victory for businesses and for economists and politicians who believed in the idea of laissez faire economics, or limiting governmental interference into the running of businesses. Joseph Lochner owned Lochner's Home Bakery in Utica, N.Y. His workplace was governed by the New York Legislature's Bakeshop Act of 1895, which provided for regulation for health conditions in the state's bakeries; one of the prime provisions of the act was a 10-hour-a-day or 60-hours-a-week limit on work that could be done by an employee.

At the time, many bakeries were not standalone businesses but rather large rooms on the bottom floor of buildings that were otherwise living spaces. In general, these spaces made poor workplaces: ceilings were low (so many workers had to stoop), windows were few and ventilation limited (so much of the dust from the wooden floor and fumes from the ovens didn't escape), workers were at the mercy of the elements (hot summers and cold winters), and sanitation was limited. Some workers slept in the bakeries; some of those people had animals for roommates because the tenement owners kept domestic animals there. In 1899, Lochner was indicted on a charge of violating the Bakeshop Act because one of his employees had worked more than 60 hours in a week; Lochner was found guilty and paid a fine of $25. In a similar scenario two years later, Lochner paid a fine of $50. The second time, Lochner appealed the conviction.

The Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court upheld the conviction, citing the Bakeshop Act's maximum of a 60-hour work week. Lochner appealed to the state's highest court, the New York Court of Appeals, which agreed with the lower court. Not content, Lochner appealed again, to the U.S. Supreme Court, which agreed to take the case. Before the Court, Lochner's attorney, Henry Weismann, argued that his client had a right to make a contract with his employees and that the Bakeshop Act's setting of a maximum hours per work week violated Lochner's Fourteenth Amendment to due process of law. The Fourteenth Amendment, passed in 1868 as one of a trio of "Civil War Amendments," extended to residents of states the same kind of protection that residents of the nation had under the Fifth Amendment. In particular, Lochner's attorney argued that his client should be protected under this wording from the Fourteenth Amendment: "... nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law." This phrasing, similar to wording in the Fifth Amendment, was known as "the due process clause." Lochner should be free to enter into a contract with his employees without having to limit their working hours, if the employees so chose to work long hours, Lochner's attorney argued. By contrast, N.Y. Attorney General Julius Mayer argued that the Bakeshop Act was clearly a health measure and fell within the state's police powers; Mayer also argued that the burden of proof was on Lochner to prove that the Bakeshop Act was unconstitutional and that the State of New York did not have to prove its law constitutional. Of the nine Justices on the Supreme Court, five agreed with Lochner. Writing for the Court, Justice Rufus Peckham said, in part: "The question whether this act is valid as a labor law, pure and simple, may be dismissed in a few words. There is no reasonable ground for interfering with the liberty of person or the right of free contract by determining the hours of labor in the occupation of a baker. ... It is a question of which of two powers or rights shall prevail–the power of the State to legislate or the right of the individual to liberty of person and freedom of contract." This decision built on an 1897 decision, Allgeyer v. Louisiana, in which the Court had agreed with the argument that the due process clause protected the right to enter into a contract. At the same time, however, the Court had cautioned that a state's right to protect its citizens' safety and happiness–the so-called "police powers"–must come into play as well. The very next year, in Holden v. Hardy, the Court found no problem with a law that mandated a maximum of eight workings hours a day for miners in Utah. Yet in the Lochner case, the Court found that the state was unnecessarily exercising its "police powers" to interfere with the legitimate doing of business. In part, the Court argued that bakers did not work in an environment as hazardous as did miners. The Court ruled that the maximum hours per week provision of the Bakeshop Act was unconstitutional. Chief Justice Melville Fuller joined the majority, as did Justices David Brewer, Henry Brown, and Joseph McKenna. Opposing were William Day, John Marshall Harlan, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Edward White. Harlan wrote the main dissenting opinion, agreeing with the State of New York that Lochner should have had to prove the Bakeshop Act unconstitutional in order to avoid conviction. Harlan also included in his dissenting opinion a number of statistics showing the health risks that bakers faced. Harlan wrote, in part: "Let the state alone in the management of its purely domestic affairs, so long as it does not appear beyond all question that it has violated the Federal Constitution. This view necessarily results from the principle that the health and safety of the people of a state are primarily for the state to guard and protect." Holmes wrote a very short opinion of his own, one that has become famous in the annals of High Court lore. Holmes was incensed that the majority seemed to be taking sides in the debate over economic policy. Holmes wrote, in part: "A constitution is not intended to embody a particular economic theory, whether of paternalism and the organic relation of the citizen to the State or of laissez faire." The Supreme Court went on during the next couple of decades to issue more opinions of a similar nature, invalidating federal and state laws that sought to regulate working conditions. The first such law that the Court upheld was a state minimum wage law in Washington in 1937 (West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish); by that time, the membership of the Court had entirely changed. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2025

David White