John Colter: Death-defying Mountain Man

John Colter was one of America's first Mountain Men. A survivor of three near-death encounters, he is thought to have been the first white man to see what is now Yellowstone National Park, Jackson Hole, and the Grand Tetons.

Colter was born in Stuarts Draft, Va., in 1775. In his first decade of life, he moved with his family to what became Maysville, Ky. Not much else is known of life until 1803, when he signed up to accompany Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and the Corps of Discovery on their famous journey through the Louisiana Territory to the Pacific Ocean. Colter was living in Kentucky when he met the expedition leaders. Colter proved to be a good hunter and tracker, and he helped the explorers navigate through the daunting heights of the Rocky Mountains. He had success in dealing with Native Americans as well, and this came in handy a few times along the way. He was one of a handful of explorers who, once the Corps of Discovery reached their destination at the mouth of the Columbia River, continued to the western coastline of North America. It was not the last time that he would leave the main group. The Corps of Discovery set out for home in 1806, reaching a number of Mandan villages in what is now North Dakota in August. There, the explorers met two of their own, Joseph Dixon and Forrest Hancock. These trappers were headed west, into what is now Montana, in search of furs, and they were after a guide to take them there. Colter volunteered, and Lewis and Clark let him go. Colter accompanied Dixon and Hancock for a few months but left them in spring 1807, striking out on his own. He built a canoe and took off down the Missouri River, bound for St. Louis. It took him quite awhile to reach his destination.

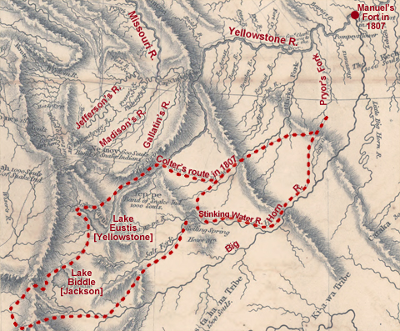

When he reached the mouth of the Platte River, he encountered a trapping party led by the famous Manuel Lisa, who asked Colter if he would go back the way he had come, again acting as a guide. Colter agreed. After a few close encounters with hostile Native Americans, they reached Fort Raymond. From there, they set out across the wilds. Lisa sent Colter on ahead. He was to explore and report back and, if he met Native Americans, invite them to bring their furs to Fort Raymond. Colter took with him a gun, some ammunition, a few gifts for Native Americans, and a small amount of supplies. During the winter of 1807–1808, he traveled nearly 500 miles on foot, through what is now Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. In exchange for Colter had not had his last adventure. Just a few weeks after he returned to Fort Raymond, he was back on the road, acting as a guide for a group of Crow and Flathead back to the fort. They didn't make it because they were attacked by a very large force of Blackfoot Native Americans. Many people died in the attack. Colter survived, sustaining being shot in the leg, and made it back to the fort.

Even this wasn't enough to keep him out of the wild. Later that year, he and fellow trapper John Potts went along the Madison Fork River, into territory controlled by Blackfoot. They were rowing boats in a waterway when they were surprised by another large party of Blackfoot, who told them to surrender. Colter complied; Potts did not. Potts died in a firefight that followed, as did a Blackfoot. His relatives wanted to kill Colter, but a chief suggested a slightly different approach. After being stripped of his clothes and all of his possessions, he was told to run. Chasing him were a group of Blackfoot warriors, who stayed just far enough behind Colter to keep him worried about getting caught. At one point, one of the warriors caught up to Colter and the two fought hand-to-hand. Colter was the one who came out of that encounter alive. In desperation, he took refuge in the very cold water of a nearby waterway, floating just beneath surface, hiding among floating logs. He somehow avoided detection by the warriors who caught up to him and set off again. He then dragged himself at great personal cost through another 300 miles of dangerous territory and made it back to Fort Raymond without further incident. Colter recovered well enough to get back on the road but encountered yet another hostile band of Blackfoot warriors. Five of his trapping companions died in the attack; again, Colter survived where others did not. He made it back to Fort Raymond and promptly declared that enough was enough. Two days later, he set off for St. Louis, canoeing down the Missouri River. He made it there safely. He got married and settled down to a quiet life. He didn't live very long, dying after contracting jaundice. He was 38 when he died, in 1813.

He left no written records of his travels, however, and so many doubted his claims. He did have an extended conversation later with William Clark, who wrote down what he heard and drew a map that he thought approximated Colter's journeys west. In the 1930s, a family in Idaho found buried a small human head-shaped stone into which were carved "John Colter 1808." The stone can be seen in a Grand Teton National Park museum. Colter's explorations were an inspiration for an entire generation of trappers, traders, and Mountain Men. His feats of human endurance were the inspiration for even more people. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

food and shelter from the Native Americans he met, he traded beads, knives, and tobacco. In the spring, he made it back to Fort Raymond, telling stories of geysers and hot springs. The people who heard those stories didn't quite believe him and referred to this supposed land as "Colter's Hell." It later turned out that Colter had visited the Yellowstone Valley; he is thought to have been the first European to do so.

food and shelter from the Native Americans he met, he traded beads, knives, and tobacco. In the spring, he made it back to Fort Raymond, telling stories of geysers and hot springs. The people who heard those stories didn't quite believe him and referred to this supposed land as "Colter's Hell." It later turned out that Colter had visited the Yellowstone Valley; he is thought to have been the first European to do so.