The Haymarket Square Riot and Aftermath

The Haymarket Square Riot, on May 4, 1886, killed more than a dozen people and injured more than 100. A subsequent trial resulted in a handful of convictions and a few executions. The result of overall labor unrest in Chicago, the Riot served as a rallying cry for workers for years to come. The United States at the time was more and more a melting pot, as immigrants (primarily from Europe but also from other continents) streamed in, pursuing the American Dream. The Statue of Liberty hadn’t been built yet, but the U.S. was already seen as a land of opportunity by many who braved rough seas to land in America. Chicago was (and still is) one of the largest cities in the country, and the city had a large number of immigrants from Europe, particularly Germany. Many of these immigrants, along with other Americans who born in the U.S., worked long hours for sometimes little money. It was not uncommon at this time for employers to expect their employees to work a six-day, 60-hour week. The Illinois Legislature had passed a law mandating an eight-hour work day, in 1867. However, many Illinois businesses, particularly in Chicago, refused to comply. Membership in labor unions had grown considerably in the second half of the 19th Century. The largest union at that time was the Knights of Labor (KOL). The KOL and other unions called for an eight-hour work day and, in 1886, issued a call for a nationwide strike to publicize this effort. The date of the strike was set for May 1. On that day, workers went on strike around the U.S., skipping work to attend rallies at which many shouted “Eight-hour day with no cut in pay” and other slogans. Some estimates have the number of striking across the country at 500,000. Business owners’ response to the ongoing unrest was, in many cases, to lock out workers or threaten to (or actually) fire them. Many businesses employed their own private security firms to keep striking workers from forming picket lines around businesses. Some businesses employed “replacement workers” to do the work that the striking workers were not doing. Security police also protected these replacement workers as they crossed picket lines that did form.

In Chicago on that day in 1886, the number on strike has been estimated at up to 40,000. Workers in that city also gathered two days later, at a harvesting machine company plant that had locked out its workers for a number of weeks. Spies, the newspaper editor, spoke to the large number of workers gathered at that rally, urging them to stand with one another in the fight for better working conditions and better pay. Spies did not advocate a violent strategy, but the rally ended in violence. A group of workers rushed the building; security police responded by firing into the crowd of onrushers. Two workers were killed.

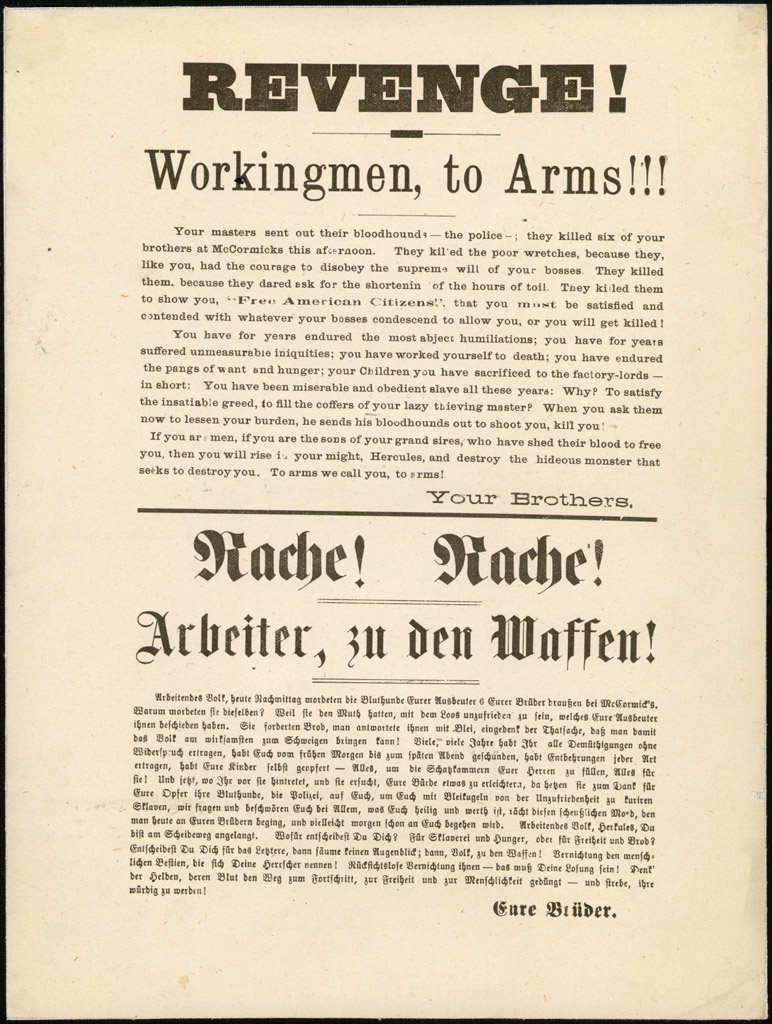

August Spies and others called for an even larger rally the next day, in Haymarket Square, a commercial center in the heart of the city. A group of people printed and distributed a flyer urging workers to attend. The flyer, printed in English and German, urged workers to seek justice for the workers who were killed. Also on the flyer were the words “Workingmen Arm Yourselves.” Spies, who did not participate in the creation or distribution of the flyer, implored the flyer creators to remove the words urging militancy, and this was done, but not before many people had seen the original flyer. The rally on May 4, 1886, was at night. Some estimates say that up to 3,000 people were in attendance. A few hundred police officers were on hand but stood well away from the proceedings. Spies addressed the crowd, as did two other labor leaders, Albert Parsons (a newspaper editor from Alabama) and Samuel Fielden (a British socialist). None of them urged violence.

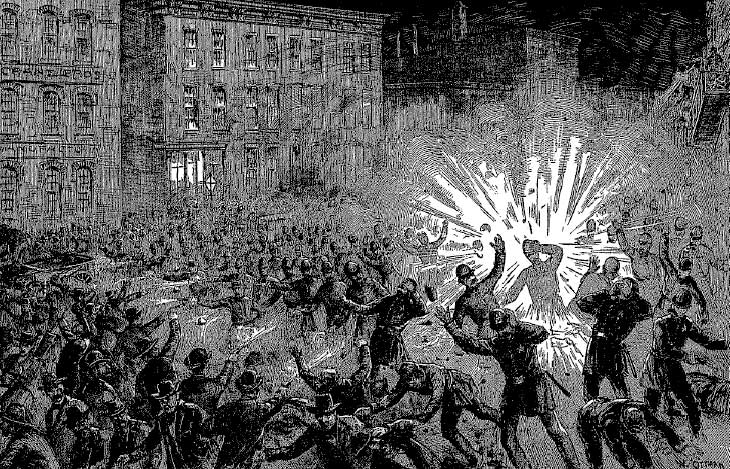

The rally lasted more than a hour. Mayor Carter Harrison attended. A light rain was falling when the rally began. Spies spoke, then Parsons spoke for a long time. By the time that Fielden got up to speak, the weather conditions had gotten worse and the crowd had thinned considerably. Most of the crowd, including the mayor, had left. When Fielden finished speaking, police moved in and asked the crowd to disperse. As the crowd was leaving, someone (and after all these years, no one has been able to prove who) threw a bomb into the ranks of police officers. The bomb blast was loud, and the crowd fled in panic. The police officers responded by shooting, and some in the crowd fired back. The crowd quickly thinned. Eleven people died. Seven of the dead were police; the other four dead were workers. Several dozen people were wounded. The name of police officer Mathias Degan, who was killed immediately by the bomb blast, has continued to be known; the names of the others killed in the blast and the resulting shots fired are footnotes in history. Chicago law enforcement officials arrested hundreds of labor leaders and other prominent members of the labor movement. Some of those arrested were known violent agitators. Many of those arrested were not born in America. Distrust of immigrants grew after this.

Attorneys for the defendants appealed the verdicts, and the Supreme Court of Illinois affirmed the original verdict. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case. One of the men, outspoken anarchist Louis Lingg, killed himself rather than face execution. Illinois Gov. Richard Oglesby commuted the sentences of two more (Fielden and Schwab, an editorial assistant to the newspaper editor Spies) to life imprisonment. But on Nov. 11, 1887, Parsons, Spies, Adolph Fischer (a typesetter at Spies’ newspaper), and Engel were hanged. A later governor, John Altgeld, pardoned Fielden, Neebe, and Schwab in 1893. Later investigations found bias toward the prosecution in the jury, in the judge, and even in the bailiff. Distrust of law enforcement grew, as did the strength of the labor movement. The first international May Day took place on May 1, 1890. Workers around the world gathered to publicize their aims and claims. The eight-hour work day eventually became a reality.

A monument to the police officers killed in the riot appeared at Chicago Police Headquarters in 1889. Investigators and historians have identified many suspects through the years, but no evidence clearly linking anyone (including those convicted) to the bombing has yet been found. The one exception is this: Fragments of the bomb removed from police officers killed in the blast matched materials found in the home of Lingg, who was known to have made bombs before; and it was Lingg who chose to avoid the hanging by ending his own life. But even in this case, no straight line can be drawn. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

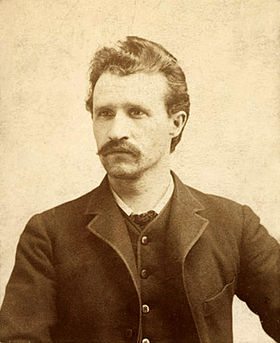

The labor movement was not the only anti-establishment movement flourising in Chicago or the U.S. at this time. Advocates of socialism and anarchy were numerous. One of the most prominent was August Spies (right), editor of Arbeiter-Zeitung (Workers Times), a German-language newspaper in Chicago. Many reports have tied Spies to a militant part of the labor movement. It was not uncommon at this time for violence to occur at rallies and for both workers and security police to wield weapons. Anarchists sometimes advocated the overthrow of the government and other forms of authority.

The labor movement was not the only anti-establishment movement flourising in Chicago or the U.S. at this time. Advocates of socialism and anarchy were numerous. One of the most prominent was August Spies (right), editor of Arbeiter-Zeitung (Workers Times), a German-language newspaper in Chicago. Many reports have tied Spies to a militant part of the labor movement. It was not uncommon at this time for violence to occur at rallies and for both workers and security police to wield weapons. Anarchists sometimes advocated the overthrow of the government and other forms of authority. A grand jury, aftering hearing testimony from 54 members of the Chicago Police Department and 64 members of the public, indicted 31 people suspected of violence in connection with the bombing. Among those indicted were Fielden, Parsons, and Spies, the three men who had spoken at the May 4 rally. Eight people (known later as the “Chicago Eight”), including George Engel (a militant radical who was nowhere near the rally), were convicted; seven were sentenced to death, and the other (Oscar Neebe) was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

A grand jury, aftering hearing testimony from 54 members of the Chicago Police Department and 64 members of the public, indicted 31 people suspected of violence in connection with the bombing. Among those indicted were Fielden, Parsons, and Spies, the three men who had spoken at the May 4 rally. Eight people (known later as the “Chicago Eight”), including George Engel (a militant radical who was nowhere near the rally), were convicted; seven were sentenced to death, and the other (Oscar Neebe) was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

A monument to those convicted after the Haymarket Square Riot appeared in 1893 in Waldheim Cemetery, in Forest Park, Ill. The monument is next to the graves of those executed.

A monument to those convicted after the Haymarket Square Riot appeared in 1893 in Waldheim Cemetery, in Forest Park, Ill. The monument is next to the graves of those executed.