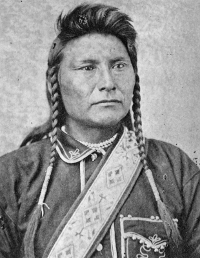

Chief Joseph was the leader of a tribe of Nez Percé who lived in the Pacific Northwest in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. He was known for his leadership during an incredibly difficult time, his bravery in the face of a daunting and harried pursuit, and for the famous speech that he gave when he finally surrendered.

In the Wallowa Valley, in what is now northeastern Oregon, was the tribe into which Joseph was born, in 1840. His father, Tuekakas, was also known as Joseph because he had taken that name in 1838, after accepting the teachings of a Christian missionary, Rev. Henry Spalding, and being baptized into the Christian religion. The boy's birth name was Him-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt, which is, in English, "Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain." Old Joseph, as Tuekakas was known, was the leader of the tribe, and he and his wife, Khap-khap-on-imi, had seven children in all.

More and more Europeans and Americans came through the area in the wake of the Lewis and Clark expedition. It wasn't long until a number of these newcomers wanted to settle in the area. As had happened elsewhere in the U.S., the federal government entered into settlement negotiations with the Nez Percéleaders. In this case, the federal official was Isaac Stevens, the governor of the Washington Territory.

In 1855, Joseph the Elder, as Old Joseph was also known, signed the treaty; some (but not all) other tribal leaders signed on as well. The treaty designed a reservation specifically for Nez Percé tribes, in an area of 7,700,000 acres in what is now Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. Most pleasing to Joseph the Elder, the allocation included the Wallowa Valley, his tribe's ancestral home. Joseph's tribes and several others moved to the reservation. Things changed in 1863, when gold was discovered nearby. A new rush of visitors turned into a new wave of people requesting settlement, including on Nez Percé reservation lands. A group of government commissioners agreed to build schools and a hospital and to provide other financial incentives to tribal leaders in exchange for the promise of moving to the new, much smaller location. This time, Joseph the Elder did not agree. A number of other tribal leaders joined him in this version of protest. Their conformance created a new rift within the Nez Percé community. Joseph the Elder died in 1871, unmoved and unrepentant. Embittered by what he saw as a betrayal by the Americans, he refused to acknowledge the American flag or the Bible. He made a point of resisting settlement encroachment as peacefully as he could. His son Joseph the Younger succeeded as leader of the tribe when his father died and followed his father's path of nonviolence.

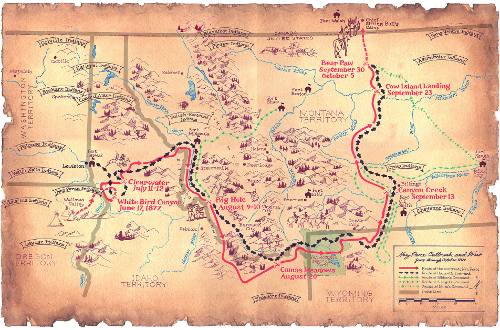

The new Chief Joseph entered into negotiations with European-American settlers in good faith; time and again, his faith was not rewarded. Yet he maintained his policy of not advocating reprisals. He feared a wholesale military response to any sort of violence on the part of his people. Some younger, more brash members of the tribe, including his younger brother Olikut, began to advocate the use of violence. In 1873, Chief Joseph secured a promise from U.S. government officials that they could stay in the Wallowa Valley. The government officials broke that promise four years later. Army General Oliver Howard arrived and delivered to Chief Joseph the message that if he and his people and the members of the other tribes who hadn't moved to the smaller reservation didn't relocate to a new home in relatively faraway Idaho within a month, they would be forced out. Joseph called a tribal council, during which several in the tribe voiced their desire to stay and fight. Joseph knew that he didn't have a force large enough to challenge Howard and his soldiers and said so forcefully; most of the tribe agreed, so they all made plans to leave. During the trip east, a group of young warriors attacked and killed a group of white settlers. The response from the U.S. Army was swift. A large force set out to chase down the Nez Percé. Joseph and Olikut, his younger brother, led their people in a forced march nearly 1,200 miles, with a group of American soldiers stalking them. The Americans had the numbers and the ammunition: 2,000 soldiers bearing arms and horses. The Nez Percé had no such numbers: 700 people, only 200 of whom were warriors. Yet in four major battles and a large handful of other smaller skirmishes, Joseph and his people succeeded in escaping time and again.

The goal of the Native Americans was to meet up with a group of Lakota Sioux who had joined Sitting Bull in Canada. The Nez Percécame close, to within 40 miles of the Canadian border, before Joseph, after fighting yet another harsh battle, formally surrendered. A group of warriors held off a surprise attack from U.S. cavalry forces long enough for more than 150 men, women, and children to escape undetected into Canada, and then Joseph gave the order to lay down arms. The date was Oct. 5, 1877. They had traveled and fought for three months, through the impending winter and across rugged terrain to what is now Montana, and had lost several fierce warriors, his brother and another chief, Looking Glass, among them. Joseph met with U.S. officials, who agreed that the Nez Percé who remained could spend the winter nearby and then return in the spring to the reservation that they had been told to live in. During this meeting, Chief Joseph gave his famous speech: “Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have it in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed; Looking Glass is dead, Ta-Hool-Hool-Shute is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led on the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets; the little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are — perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever." Despite what the officials who met with Chief Joseph might have promised him, the reality was that the Nez Percé would have to wait a bit longer before returning west. Instead, they were treated as prisoners of war and held in the federal prison at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for several years before being transported to Indian Territory. Many of them died from a variety of causes, malaria being one of them.

During this time, Chief Joseph, who had become famous in the East, issued appeal after appeal for better treatment for his people. His leadership during the extended retreat into Montana and his surrender speech had earned him respect. He was given leave to travel to Washington, D.C., and even to meet with President Rutherford B. Hayes. Chief Joseph also pleaded his case in the press, giving an interview to the North American Review in April 1879. It took awhile, but he finally won his people the right to return home. In 1885, a federal official gave the order for the Nez Percé to return to their tiny reservation in the Pacific Northwest. The final betrayal that Joseph himself and his tribe were sent to the Colville Reservation, in northeast Washington. He lived out his life there, never seeing his homeland again. He died on Sept. 21, 1904. He was 64. A friend and fellow chief, Yellow Bull, said in his eulogy, "Joseph is dead, but his words will live forever."

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

had a great many horses of which we gave them what they needed, and they gave us guns and tobacco in return. All the Nez Perce made friends with Lewis and Clark and agreed to let them pass through their country and never to make war on white men. This promise the Nez Perce have never broken."

had a great many horses of which we gave them what they needed, and they gave us guns and tobacco in return. All the Nez Perce made friends with Lewis and Clark and agreed to let them pass through their country and never to make war on white men. This promise the Nez Perce have never broken." The various Nez Percé tribes lived in what is now Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington. The first known encounter between these tribes and European-Americans was in 1805, when members of the

The various Nez Percé tribes lived in what is now Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington. The first known encounter between these tribes and European-Americans was in 1805, when members of the