Charles Lindbergh was the first pilot to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. He did this in 1927.

Airplanes were still a relatively recent invention at that time. Lindbergh, born in 1902, began flying when he was 20, touring the United States as a stunt flyer in a Curtiss "Jenny" biplane that had survived World War I. A top-of-the-class status as a graduate in the Army Air Service flying school in Texas got him a job as an airmail pilot in 1926, flying regularly between St. Louis and Chicago. Lindbergh's wasn't the first transatlantic flight. That honor belonged to Brits John Alcock and Arthur Brown, who flew from Newfoundland to Ireland on June 15, 1919. They made their flight in a Vickers Vimy, a twin-engine bomber of a type that was developed for World War I but didn't see any action. Alcock and Brown removed the bomb racks in order to add extra fuel tanks. They sat in an open cockpit at the front of the plane. About 16 hours after they took off, they touched down in a bog. They had flown 1,960 miles. A French hotel owner named Raymond Orteig announced a prize of $25,000 for the first pilot or team who could fly nonstop from New York to Paris, or vice versa. Lindbergh took up the challenge, as did several other pilots. Lindbergh had graduated first in his class from the U.S. Army flying school in 1924. He survived a midair collision with another plane in 1925 and then found work as a postal pilot, flying from St. Louis to Chicago. He also had a reputation as a barnstormer and a daredevil. He twice flew a doctor across the flooding Wisconsin River in order to answer emergency calls. By 1927, when he was preparing for his famous flight, four people had died and three had been seriously injured in taking up pursuit of what came to be called the Orteig Prize.

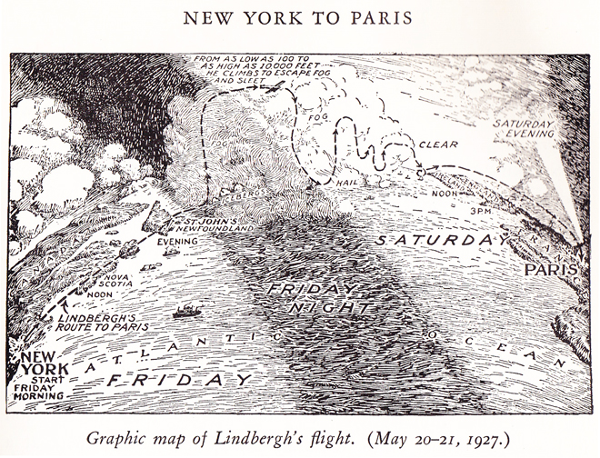

Lindbergh planned to do things a bit differently from the way that others had. He planned to fly by himself; previous flight attempts had all included a pilot and copilot. As well, Lindbergh was intending to fly his single-engine plane; previous attempts had featured multi-engine planes because the pilots thought that they needed more than one engine in order to complete the flight. Most dangerously, Lindbergh had rejected the inclusion of a parachute and even a radio in order to include more gasoline. Some newspapers labeled him "the flying fool." Lindbergh was not to be deterred, but he did have to wait a few days because of bad weather in New York. He took off on his historic flight at 7:52 in the morning on May 20, 1927, from Roosevelt Field on Long Island. Rain the previous night made the takeoff a bit difficult, as did the heaviness of the payload: 450 gallons of fuel weighed down the plane, the Spirit of St. Louis. He cleared a telephone line and some trees by only 20 feet, then took to the air, flying over Cape Cod and Nova Scotia and then out to sea. The crowd of 500 who had gathered to see him off held their breath and then cheered. He ascended to 10,000 feet in order to get above fog, resisting the urge to fly through storm clouds after an encounter with sleet during a brief foray into a cloud. Brief detours around some clouds made his journey that much longer.

Lindbergh wasn't always so far above the surface. At times, the plane was only 10 feet above the surface of the waves, again in a attempt to circumvent the difficulties presented by a thick fog. Lindbergh struggled to stay awake a few times during his historic flight. That was when skies were clear. The appearance and reappearance of fog kept him active. Just before 8 p.m., he rose from 800 feet to 7,500 feet in order to stay above fog clouds. Just an hour later, he saw ice forming on the wings and turned back for a time. He also kept the windows open at times, on the theory that the cold would keep him awake. He flew over Ireland and England, 1,500 feet off the ground. He flew across the English Channel and honed in on the lights of France. He flew low over a number of fishing boats but did not see anyone appear. He made it the rest of the way to Paris without incident, landing at the Le Bourget Aerodrome at 10:22 p.m. He had flown the 3,610 miles in 33.5 hours.

Officials at the Paris airfield where Lindbergh landed had provided ropes in order to keep out what turned out to be a large, adoring crowd that numbered nearly 100,000. He had taken advantage of the headlights of the cars that that crowd had driven because the airfield wasn't on his map. The ropes were not sufficient to their intended purpose. The crowd dragged Lindbergh off the plane and carried them above their heads for several minutes, before French police took charge of Lindbergh and carried him to safety. Some in the crowd turned souvenir-hungry and damaged the Spirit of St. Louis in the process. At a ceremony the next day at the American Embassy, Lindbergh enjoyed a sustained ovation from another large crowd, who stayed for hours waiting to see the famed aviator again. He stayed several days in France and enjoyed the Legion of Honor (usually reserved for heads of state), pinned on him by the country's president, Gaston Doumergue.

Lindbergh was a huge hit in France, possibly even moreso than in the U.S. When he returned home (on a Navy cruiser, not in a plane), he went on a nationwide tour, stopping in 92 cities in all 48 states. President Calvin Coolidge awarded him the Medal of Honor and the Distinguished Flying Cross. He flew to other countries, including Mexico, where he met Anne Morrow, whom he would later marry. The U.S. Post Office issued a special air mail stamp depicting Lindbergh and his famous plane. He was no longer "the flying fool." Instead, he was now "Lucky Lindy" and the "Lone Eagle." |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2025

David White