Booker T. Washington: Guiding Light of Education

Booker T. Washington worked his way up from slavery to head of an educational institute and became one of the most famous African-Americans in the history of the country.  Young Booker, who was born Booker Taliaferro in 1856, spent his early years in a one-room log cabin, which doubled as the kitchen for the plantation. His mother, Jane, was enslaved to a plantation owner in Franklin County, Va. He never knew who his father was. To bring in money for the family, Booker got a series of manual labor jobs, carrying sacks of grain and and working in salt mines and coal mines. At one place, he worked with his stepfather, Washington Ferguson, whom Booker's mother married after she moved to Malden, W.Va., at the end of the Civil War. Booker was a curious boy and wanted to know more about the world around him. Before he was a teenager, he was getting up before dawn to study, using a book his mother had bought him in order to learn how to read and write. He got a job as a houseboy in 1866, about the same time that he took his stepfather's last name, Washington, as his own. But his work in the house of Viola Ruffner convinced him even more that he needed more of an education. So, at age 16, he left his family and traveled 500 miles to Hampton Normal Agricultural Institute. (Having very little money, Booker walked those 500 miles, taking odd jobs along the way.) Booker helped pay for his education by taking a job as a janitor at Hampton. His solid work ethic and enthusiasm for learning gained the attention of the headmaster, former Union General Samuel Armstrong (himself a commander of African-American soldiers during the Civil War), who arranged for a scholarship. Just three years after he arrived at Hampton, Booker graduated, with impressive grades. He started to give back to the education community by teaching at a grade school in Malden, W.Va., that he himself had attended. He also furthered his studies at Wayland Seminary, in the nation's capital. In 1879, Armstrong offered Washington a job teaching at Hampton. The headmaster continued to provide opportunities for his former pupil, naming Washington as head of the newly created Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, in 1881. It was there that Washington made a name for himself, building Tuskegee up from a tiny school with classes in an old church on borrowed land to one of the most recognized educational institutions in the country. Hundreds of students attended classes on a growing campus, spread over 540 acres of land. Tuskegee students attended academic classes as well as more labor-intensive classes such as brickmaking, cabinetmaking, carpentry, and shoemaking. Washington became nationally known, in particular for a major 1895 speech later called the Atlanta Compromise, in which he stressed the importance of vocational education as a means to increasing opportunities for African-Americans. His networks included wealthy whites and blacks in business and religious circles, as well as a large part of the black community in general. As the 20th Century dawned, he helped form the National Negro Business League. Also at this time, he wrote his autobiography, which was published first in The Outlook, a magazine, and then as the book Up from Slavery, which is still widely read. He wrote several other books as well. He was married twice, to Fannie Smith in 1882, Olivia Davidson in 1885 (a year after Fannie died), and Margaret Murray in 1893, (four years after Olivia died). In all, Booker had three children: Portia (with Fannie) and Booker T. Washington Jr. and Ernest Davidson Washington (with Olivia). Margaret helped rear all three children. Well-known for touring the country to give lectures and raise money (including for securing large donations from such famous men as steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie, Standard Oil giants John D. Rockefeller and Henry Rogers, Kodak founder George Eastman, and Sears & Roebuck President Julius Rosenwald), he was head of Tuskegee for nearly 40 years, until he died in 1915, at age 59. His funeral, in the Tuskegee Institute Chapel, drew more than 8,000 people. Washington's impact continued to be felt after his death, as the partnership he forged with Rosenwald had resulted in the Rosenwald Fund, which provided funding for more than 5,000 schools throughout the South. Tuskegee itself continued to expand and was the predecessor to today's Tuskegee University. When Washington died, in 1915, the Institute had a student population of 2,000, a staff of nearly 200, and an endowment of nearly $2 million.

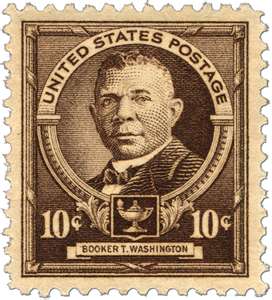

He was the first African-American to appear on a U.S. postage, on April 7, 1940, and the first African-American on a U.S. currency coin, a half dollar, from 1846 to 1954. The first major ship named after an African-American was the Booker T. Washington, christened in 1942. His name adorns hundreds of schools for all ages throughout the country. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

Washington's legacy extended far beyond the school's borders. Under his leadership, the institute began a rural extension program, so that students who could not afford to live on site could still benefit from its teachings. Tuskegee alumni also spread the word by founding smaller schools throughout the American South, always with an emphasis on training teachers. Among the most prominent alumni was noted inventor

Washington's legacy extended far beyond the school's borders. Under his leadership, the institute began a rural extension program, so that students who could not afford to live on site could still benefit from its teachings. Tuskegee alumni also spread the word by founding smaller schools throughout the American South, always with an emphasis on training teachers. Among the most prominent alumni was noted inventor