Book Review: She Stood for Freedom

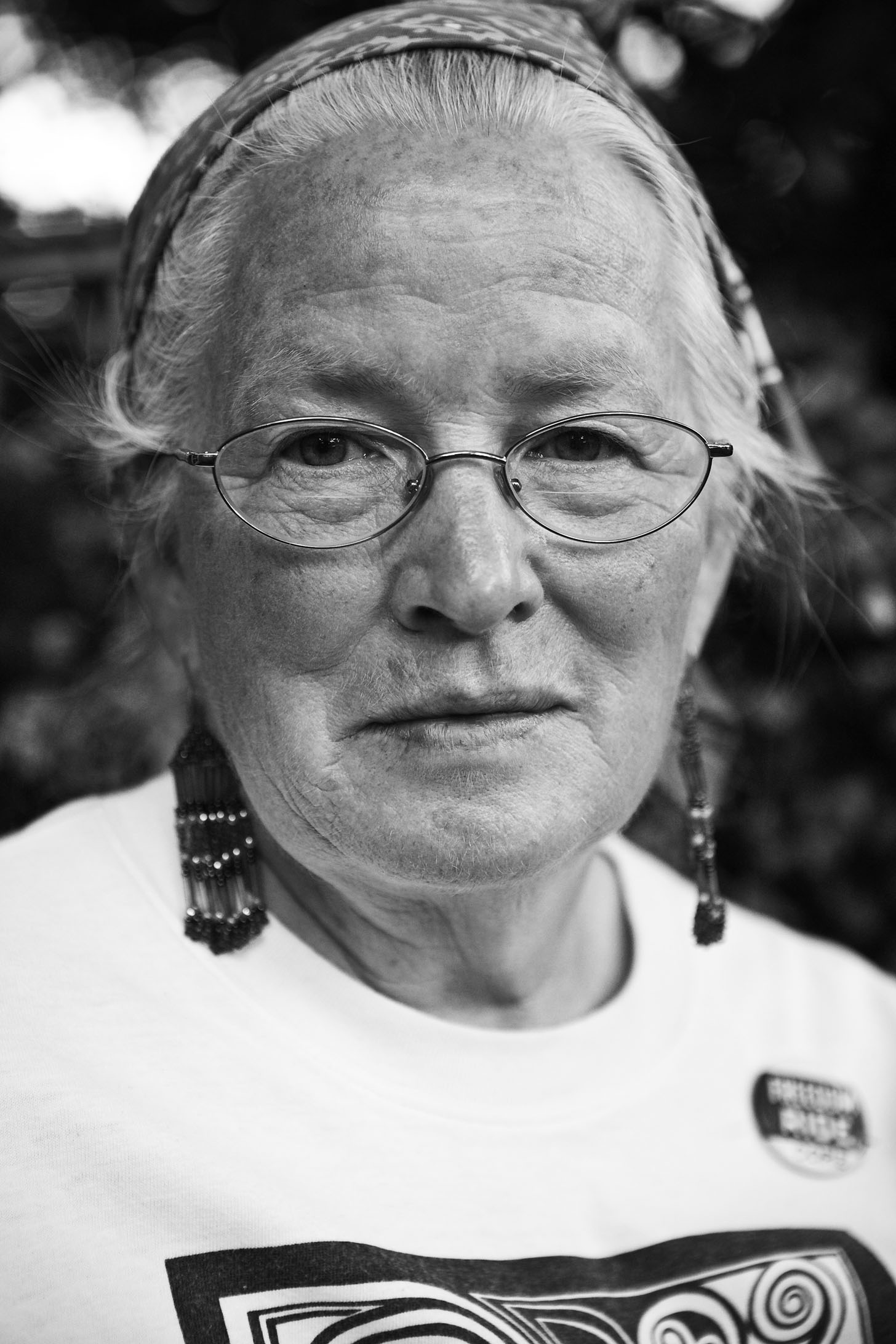

Joan Trumpauer Mulholland knows about courage. She has been demonstrating it since she was a youngster.

Born in the midst of World War II, Joan grew up in Arlington, Va., a city firmly in the Southern frame of mind as far as memories of the Civil War and as far as discrimination against African-Americans. A church-goer and dedicated student, Joan early encountered a kind of discrimination ingrained in American society when she learned that her religion taught her that everyone was equal in the eyes of the Christian God but that the laws of her country prohibited white people and African-Americans from attending the same church services. The presentation of these ideas was an especially powerful way for the author to drive home a bigger point by presenting information and then letting the reader make up his or her own mind as to what inferences to make. In this case, my inference was that the author was suggesting that the teachings of the church should match the laws of the land and, further, that the idea of all people's being equal in the eyes of God was in direct opposition to the way that many church-going people behaved toward people who had skin of a different color. That wasn't the only prohibition on the law books of many states in the Union during this time. Segregation was prominent in most of the country (not just in the South); in the South, however, it was more widespread and more protected by state laws. As well, Joan encountered people who had different views on the status of African-Americans in society. Her own mother, a Southerner, believed that white Americans were superior to African-Americans by the very nature of the skin color of the two sets of people; Joan's father, however, was a Northerner who believed in more equality of the races. Obviously, her parents had disagreements on how to treat people in their city. Joan took after her father in this regard and, spurred by her religious teachings and her respect for the Declaration of Independence's pronouncement of an equality independent of skin color, attended a dinner at her church that was also attended by African-American students. The attendees had to keep their dinner a secret, for fear of angering their parents; this was true of both the white children and the African-American children. Again, we can see the idea of opposition between church teachings and churchgoers' behavior; the author uses subtlety to let the reader make up his or her own mind.  At college in 1960, Joan officially joined the Civil Rights movement, marching with African-Americans who were protesting segregation in America. Officials at her university told Joan that they weren't happy with her actions, and her response was to move back home, to Arlington, where she participated in sit-ins with African-Americans. In a sit-in, a person sat at a lunch counter and refused to leave until he or she had been served food. Many lunch counters and restaurants would not serve African-Americans; sit-ins provoked various responses from staff and other customers. At college in 1960, Joan officially joined the Civil Rights movement, marching with African-Americans who were protesting segregation in America. Officials at her university told Joan that they weren't happy with her actions, and her response was to move back home, to Arlington, where she participated in sit-ins with African-Americans. In a sit-in, a person sat at a lunch counter and refused to leave until he or she had been served food. Many lunch counters and restaurants would not serve African-Americans; sit-ins provoked various responses from staff and other customers.

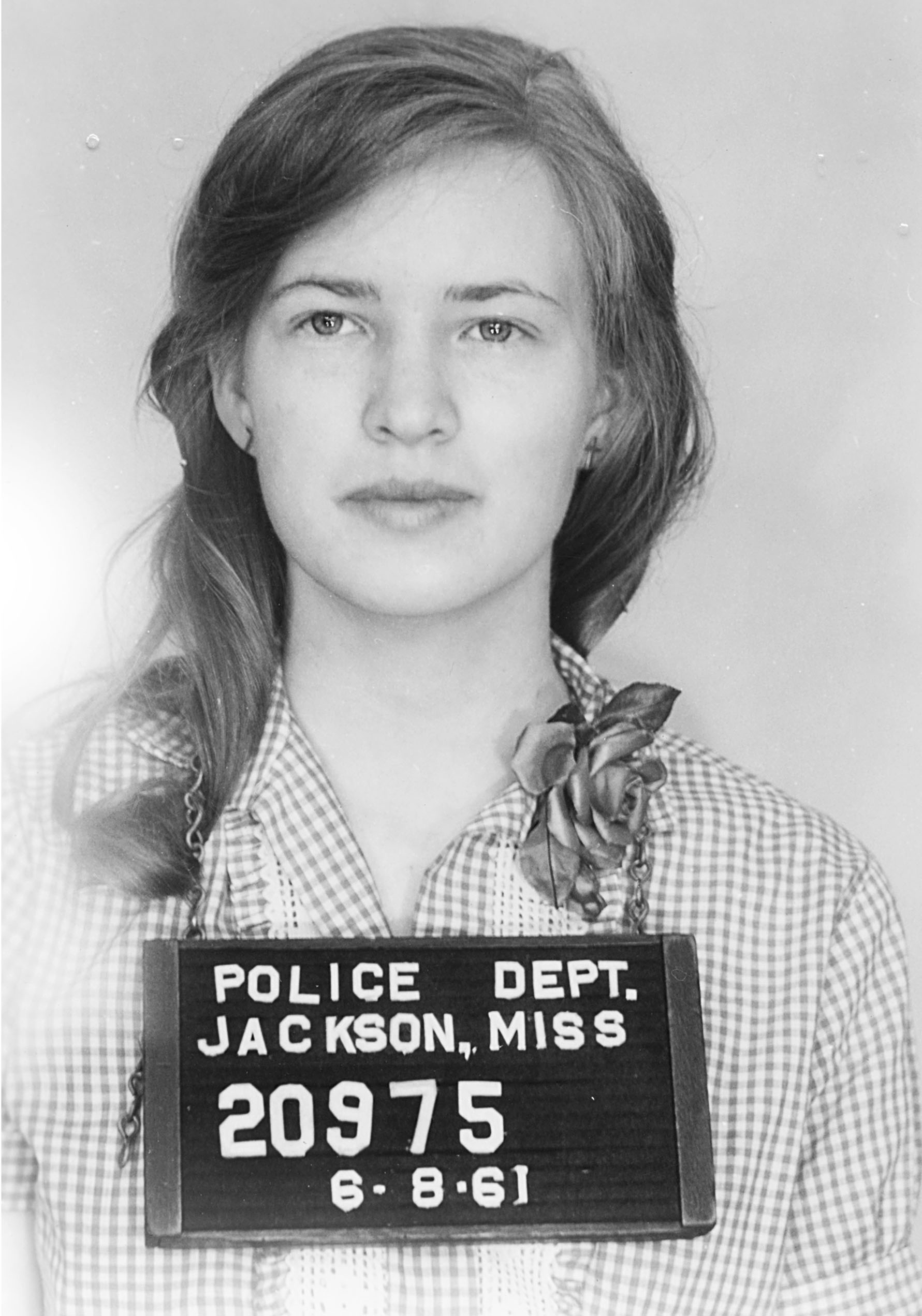

After hearing about the violence that greeted the famous Freedom Riders, Joan and some friends went to Mississippi to stage a jain-in. They protested at a train station, refused to leave, and were arrested. They refused to appeal their sentence, preferring to remain in jail in order to call attention to their cause. The author does a good job of conveying just how scary the infamous Parchman Prison was. As it turned out, the cell in which Joan stayed was right around the corner from death row. Talk about courage! Joan was eventually released from prison and made her way to Mississippi's Tougaloo College, an all-African-American school, where she enrolled for study. In a well planned illustration of irony, the author reminds us that it wasn't just white Americans who were suspicious of Joan's actions or her motives. In this case, Joan wasn't all that popular with the African-American students at first. Joan persevered, though, and eventually made friends at college. Again, the author is making a larger part by illustrating a smaller scenario.

Perhaps the most compelling use of Joan's own words is the answer that she still gives in response to the question of "Why did you do all of that?" Her response is a poem that she wrote called "Dialogue," which includes the idea that Joan had done "nothing but acted like an American." As an adult, Joan continued her efforts to promote civil rights. One of her main contributions was of memorabilia to the Smithsonian Institution, to help illustrate the trials and travails of the Civil Rights movement. And her story came full circle when she went back into the classroom, to help today's students appreciate her struggle and know how important she thought it was for them to continue. The author does us one final favor by giving Joan the last words: "You don't have to change the world ... just change your world." See also: Interview with Joan. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

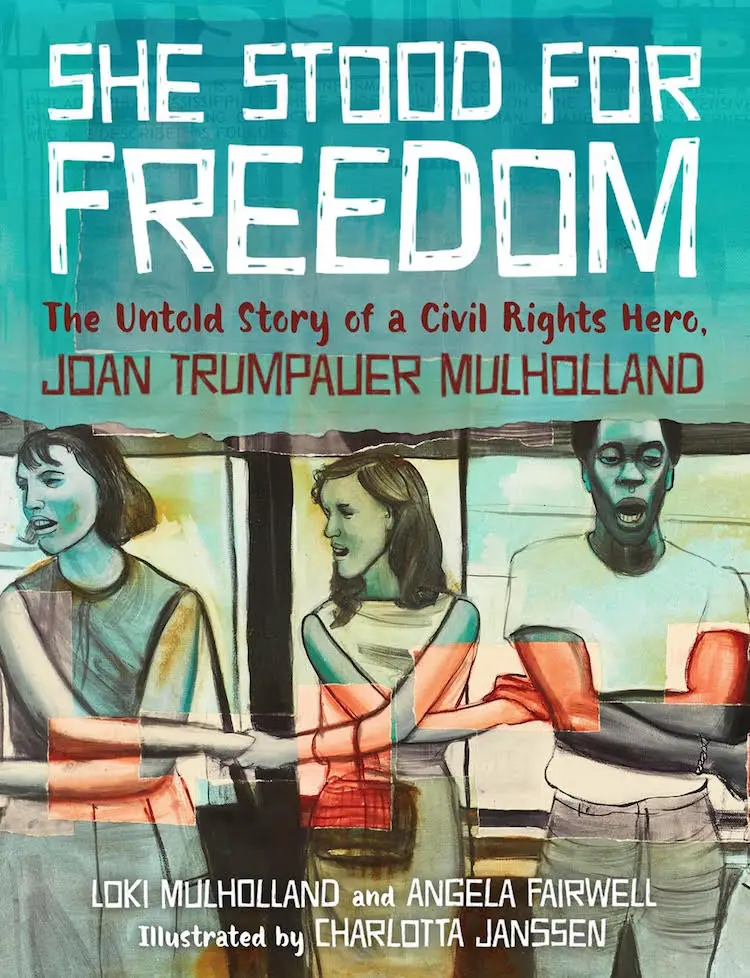

The story of Joan's activism as a young white girl in the American South in the last half of the 20th Century is a story of courage, of determination, of a desire for fairness, and of a desire for equality under the law. Her story is the subject of a book called She Stood for Freedom, by Loki Mulholland, her son, who also made a documentary titled An Ordinary Hero, and Angela Fairwell.

The story of Joan's activism as a young white girl in the American South in the last half of the 20th Century is a story of courage, of determination, of a desire for fairness, and of a desire for equality under the law. Her story is the subject of a book called She Stood for Freedom, by Loki Mulholland, her son, who also made a documentary titled An Ordinary Hero, and Angela Fairwell. Joan was in attendance at Martin Luther King Jr.'s famous

Joan was in attendance at Martin Luther King Jr.'s famous