The Unification of Germany

Part 2: Common Culture

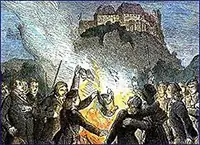

Another prime driver was cultural. The sharing of common allies and enemies had given the various German-speaking nations a sense of shared identity. As the Zollverein broke down economic and political barriers to amalgamation, the Enlightenment shone brightly on German literature, music, philosophy, and science, giving German-speaking peoples a pride in their common heritage. In the wake of newfound freedoms after the Congress of Vienna, many Germans spoke out–for political freedoms, for shared political identity, for nationalism. The Wartburg Festival in 1817 held up the famed Reformation leader Martin Luther as a sort of prototype for a uniter of German-speakers across Europe. Certainly many German-speaking states embraced the Protestant way of thinking, rejecting Catholic teachings and restrictions; such disagreements were a main factor in many wars in the late Middle Ages. This was not absolute, however, because the Holy Roman Empire was certainly Catholic and had many allies that were the same. Organizing the Wartburg Festival were students of German universities. During the festival, many of these students and others of like mind spoke out in favor of freedom and liberal ideas. They chose Wartburg Castle because Luther had hidden there during his battle with the pope and the emperor. The proceedings in 1817 consisted of speeches, a feast, and the singing of hymns.

After the official events had ended, a large group of participants staged a burning of books that they considered supportive of old, more reactionary ways. Also taking part in the festival were members of the Burschenschaften, a student organization that often favored militant means to express their strong preference for individual rights. The attendance of those students and the burning of the books caught the attention of many powerful nobles and political officials far and wide, especially after one of the students, Karl Ludwig Sand, killed a conservative writer, August von Kotzebue. Among those outraged at the activities was Klemens von Metternich, the State Chancellor of Austria, who arranged a meeting of officials from his own state, from Prussia, and from other German states. The officials met at Carlsbad in August 1819 and enacted the Carlsbad Decrees, which were a crackdown on the students who spoke out and the things for which they spoke out. Burschenschaften found themselves banned; universities were told to allow state-appointed watchdogs to stamp out other such student activity. Teachers suspected of sympathizing with such students were targeted and, in many cases, removed. As well, the Carlsbad Decrees imposed heavy restrictions on the publication of newspapers and other writings. Such measures were certainly reactions to revolutionary ideas, thoughts, and actions. However, those who wanted more individual rights and freedoms far outnumbered those in power who wanted to restrict such things. Revolutionary fervor hit France again in 1830, as the July Revolution resulted in the overthrow of an autocratic and unpopular king, Charles X, and the installation of a constitutional monarch, Louis Philippe, who had the support of the people. Other European powers contended with such pressures. Austria and Prussia alone stood fast against such change. In other German-speaking states, the calls for change were loud and clear.

Two years later, another festival caught the attention of many in German-speaking lands. The May 1832 Hambach Festival was a country fair that doubled as a vehicle for expressing nationalist and liberal sentiments. Tens of thousands of people gathered in the Bavarian town of Hambach, giving speeches, singing songs, and otherwise behaving peacefully. The subsequent march uphill to the ruins of Hambach Castle offered some people the opportunity to fly the flag of the driven-into-underground Burschenschaften. Again Metternich responded with a heavy hand, convincing the Diet to restrict political activity and speech and also gaining a concession from the member states that they would send troops to suppress any such unrest in the future. Next page > Final Acts > Page 1, 2, 3 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White