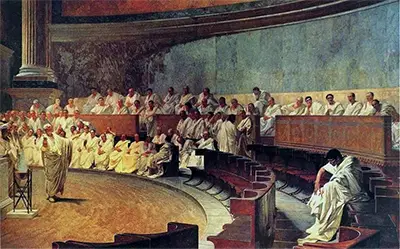

The Roman Senate

The Senate was an at times powerful legislative body in the civilization of Ancient Rome. The size and nature of its membership changed through the years. Romulus, the founder of Rome, also founded the Senate, by appointing 100 men from the settlement's most important families. These men he called Patres, or fathers; from this word came the name for the well-do-to class, the patricians. The word Senate comes from the Latin word Senex, which translates into English as "old man." (Another, perhaps more apt translation is "council of elders.") The original Senators were elders of their families. Senators were not always old. In fact, many were young. The minimum age was 32 originally; the first emperor, Augustus, changed the minimum age to 25.

Following Romulus's lead, the Senate continued to be made up of members who were appointed. An official known as a censor had the power to appoint Senators. In the early days, requirements for being eligible to be a Senator included a certain amount of wealth, usually reflected in the ownership of property, and previous experience as a magistrate (which in Ancient Rome was any type of public official, not just a judge, as the term is often used today). Anyone who had been convicted of a crime could not serve in the Senate. Through a combination of precedent and economic reality, patricians held on to sole ownership of the Senate until the Conflict of the Orders, in the 3rd and 2nd Centuries B.C. The passage of the Hortensian law in 287 B.C. ended all patrician exclusivity. Initially, a series of kings ruled Rome. During this time, the Senate had little power, serving as an advisory body for the king. Under the Republic, Senators had more power. Even then, the Senate issued decrees, which could be ignored if the ruling executives so chose. From its earliest days, the Senate had broad powers in foreign matters, however. It was the Senate that declared war and negotiated peace treaties and trade agreements with other civilizations. It was the Senate as well that looked after the city's treasury. The fifth king of Rome, known as Tarquin the Elder, added another 100 men to the Senate. His grandson, Tarquin the Proud, dispatched many of those and didn't replenish the numbers. The first Roman consuls, Lucius Junius Brutus and Publius Valerius Publicola, increased the Senate membership to 300. In later years, the number of Senators went as high as 500. A Senator most often wore a white tunic that had a purple stripe and the right shoulder, and they also wore special shoes. Senators could also wear a special ring; such rings were originally made of iron and later made of gold. Senators could spend the rest of their lives in office, unless removed for misconduct (or, during August's reign, because of a loss of wealth). Being a Senator didn't command a salary but did take up a lot of time; this was another barrier to men (for women were not permitted in the Senate) who otherwise had to spend their days working for a living. Technically, the Senate didn't have true legislative power. All potential decrees approved by the Senate had to also be approved by either the Centuriate Assembly (over which the consuls presided), depending on which jurisdiction oversaw the aspect of life covered by the proposed decree. Senate meetings had to take place within the city boundary or, at the most, within one kilometer (.62 miles) outside it. From ancient times, the Curia, in the Forum was available to the Senate, and so it often met in that building. Before each meeting began, religious officials would perform a sacrifice to the gods and then seek divine omens. The presiding magistrate (commonly one or both of the consuls) would then declare the meeting in session and after, giving a speech, direct the Senators to discuss any number of issues. Each Senator could speak on any issue, for as long as he wanted, and every Senator had to be given the chance to speak before a vote could be taken. Meetings began at dawn and had to end at nightfall, so a Senator who wanted to ensure that a vote wouldn't be taken on a certain issue could just keep talking. (This is the origin of the filibuster found in the U.S. Senate.) Voting took one of three forms: voice, a show of hands, or a physical gathering in the meeting space of those in favor of an issue and those opposed. The Senate (or a consul) could, in times of emergency, appoint a dictator, who would have full powers of consulship for six months. The Senate reserved the right to veto any decision made by a dictator. Such officials were not unknown during the first few centuries of the Republic (with Camillus being the most famous); however, after 202 B.C., the function of the dictator fell instead to the consuls, by way of an "ultimate decree of the Senate." (Before the end of the Republic, the Senate appointed just two more dictators: Sulla and Julius Caesar). With the transition into Empire, the Senate gained the power of the assemblies, which continued to meet but lost their legislative powers. One prime example of this was the criminal trial, over which the Senate presided in the Empire: A consul was the presiding officer, the Senators served as jurors, and the verdict was issued in the form of a senatorial decree. With the advent of the Emperor as the sole head of state, the Senate was again reduced in stature and power. The Emperor sometimes presided over sessions of the Senate and spoke whenever he wanted to speak. Even with the Emperor wasn't there, Senators were strongly encouraged to approve any laws that the Emperor favored; in order to indicate disfavor, a Senator would abstain rather than vote against such an imperially countenanced measure. The Senate did still have the power to try cases of treason. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White