The 1666 Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London demolished most of the city’s buildings but resulted in relatively few reported deaths. Many historians think that it was an accident waiting to happen. London, along with much of Europe, had suffered an outbreak of the Bubonic Plague, commonly known as the “Black Death,” just before the Great Fire. In 1665 alone, London reported nearly 70,000 deaths from the Plague, which was later found to have been caused by fleas on rats that came to London from elsewhere. The population of the city overall increased in 1666, to nearly 500,000. (It had been 460,000 at the start of 1665, so the outbreak of the Plague didn’t scare everyone away.) London was far and away the largest city in England at this time, and people flocked to the city at all times of the year. Construction continued to accommodate the crowds, and some building owners added increasingly risky components to their housing centers, including overhanging floors called jetties, built on top of buildings that already had six or seven storeys. King Charles II had forbidden the construction of jetties in 1661, but the jetties went up all the same. The king had also warned the London city government of the extreme risk of fire as late as 1665. Accompanying this later warning was an announcement of penalties for shoddy building. The London city government ignored this as well. Charles was King of England, but his authority did not extend, apparently, to the administration of local government affairs. The City of London proper had a largely poor population; by this time, the royalty and the aristocracy had settled, in large part, in wealthier suburbs, like Whitehall and Westminster. Through the year 1666, as the spring and summer came and went, rainfall was sparse and so temperatures were high and the ground and buildings were dry and, also, water reserves were low. That set of conditions was far from ideal in terms of fire risk, especially because many if not most buildings in the city were made of wood or pitch, both of which burned quite easily and rapidly. As well, dotting the City were foundries and shops just like the baker’s, which depended on live heat sources for their livelihood. Strict fire codes did not exist for these businesses. The city had suffered a major fire as recently as 1632; little had changed in the way of prevention measures, however.

The fire spread rapidly. Farriner and his daughter escaped the building through an upstairs window; the one person left as the building went up in flames was a maid who was too terrified to escape. Fires were not uncommon in London at this time, and so the response to this fire was not on the order of a disaster. Sir Thomas Bloodworth, the Lord Mayor of London, appeared on the scene but refused to call out the fire brigade.

A common fire-fighting tactic at this time was the demolition of buildings in the path of a fire; this created, in effect, a firebreak, removing from the fire’s path a ready source of flammable material. As the fire raged and spread all day Sunday, city officials, notably the Lord Mayor, gradually authorized the demolition of certain buildings; by this time, the fire had really gotten going. The fire continued to burn relatively unchecked on Monday, and it was on that day that a story spread through the streets that the fire had been set deliberately, by agents of another country. England had been at war with Denmark, France, and the Netherlands for the past year or so, in the Second Anglo-Dutch War. This idea of foreign intervention stoked feelings of xenophobia that smoldered for the duration of the Great Fire. Fire prevention measures proved ineffective, and the fire raged on for another day. The streets were narrow and cluttered, and these conditions hampered efforts by fire fighting crews. The Thames provided water for dousing flames, but water levels were down because of the recent drought. The city did have fire-fighting vehicles, but they were, in many cases, too wide to fit down a street that was not clutter-free. More effective were the traditional methods of using buckets and hoses and “firehooks,” which were used to demolish buildings.

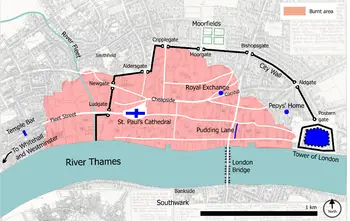

On Tuesday, the fire destroyed many landmarks, including St. Paul’s Cathedral, the General Letter Office, the Bidewell Palace, and the Custom House. The strong winds coming from the east subsided on Tuesday evening; the following day, soldiers succeeded in using gunpowder to create enough firebreaks to stem the fire’s tide. In the end, the Great Fire of London consumed more than 13,000 houses, 87 churches, and many government buildings. Death toll figures range from six to 16 or perhaps a few dozen; that is for bodies recovered, and some archaeologists are convinced that the fires burned so hot (more than 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit by some estimates) that they would have incinerated some unlucky people. Burned to a crisp were iron chains and locks on city gates and imported steel stored on wharves.

The Great Fire also eradicated all remnants of the rat and flea population that had brought the Plague to London in the first place. After all of the flames had vanished, city planners rebuilt large parts of the city, keeping in mind what had just caused so much of the destruction. The king appointed a group of commissioners to redesign the city. Among the innovations were wider streets, thicker walls, and buildings made of brick. St. Paul’s Cathedral was rebuilt. Noted architect Christopher Wren designed 50 new churches. Wren also designed the 200-foot-tall Monument to the Great Fire of London, which still stands in Pudding Lane, which is now named Monument Street. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

On the evening of September 1, 1666, a Saturday, a baker named Thomas Farriner (name sometimes spelled Farynor) closed up for the night at his shop in Pudding Lane. Reports vary as to the state of the fire that Farriner left burning in his shop. He would have normally used heat in his trade, and he would have been in the habit of extinguishing the flame before he left the shop. For whatever reason, that night, he did not.

On the evening of September 1, 1666, a Saturday, a baker named Thomas Farriner (name sometimes spelled Farynor) closed up for the night at his shop in Pudding Lane. Reports vary as to the state of the fire that Farriner left burning in his shop. He would have normally used heat in his trade, and he would have been in the habit of extinguishing the flame before he left the shop. For whatever reason, that night, he did not.  Sparks from the bakery spread across the street to straw and fodder in the stables of the Star Inn. Unchecked, the fire gained in speed and size and spread to nearby Thames Street, on which sat warehouses packed with coal, hemp, lamp oil, and tallow (for candles). About this time, a strong wind blew in from the east, and the fire became an inferno.

Sparks from the bakery spread across the street to straw and fodder in the stables of the Star Inn. Unchecked, the fire gained in speed and size and spread to nearby Thames Street, on which sat warehouses packed with coal, hemp, lamp oil, and tallow (for candles). About this time, a strong wind blew in from the east, and the fire became an inferno. Flames consumed the Royal Exchange. Bankers’ houses burned on Monday afternoon, and bankers rushed to get their gold coins to safety. Southwark, across London Bridge to the south, did not burn, thanks in large part to a firebreak that had also served a similar purpose in the 1632 fire.

Flames consumed the Royal Exchange. Bankers’ houses burned on Monday afternoon, and bankers rushed to get their gold coins to safety. Southwark, across London Bridge to the south, did not burn, thanks in large part to a firebreak that had also served a similar purpose in the 1632 fire. A large part of the inner City was demolished, through either fire or firebreaking. Many of the inner city poor who had survived the Plague the year before found themselves homeless after the Great Fire. This problem was less pronounced among the wealthy because they either had lived outside the City before the Plague or moved outside the City once the Plague hit.

A large part of the inner City was demolished, through either fire or firebreaking. Many of the inner city poor who had survived the Plague the year before found themselves homeless after the Great Fire. This problem was less pronounced among the wealthy because they either had lived outside the City before the Plague or moved outside the City once the Plague hit.