England's King Richard I Lionheart

King Richard I of England remains one of the country's famous rulers, even though his fame stems much more from what he did outside the country than in; he spent, in fact, only five months of his 10-year reign at home. Richard was born on Sept. 8, 1157, in Oxford, the third son of King Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. Richard, taking after his mother, preferred to read chivalric literature and poems; he even wrote his own poems, in both French and Occitan, a dialect of French found in romances of the time. He is most famously known as a fighter, however. He was 6-foot-4 and a tremendously skilled soldier. He was bold and charismatic and inspired loyalty in soldiers and nobles alike.

Richard was said to have tremendous courage. This was reflected in the name that he adopted, Lionheart. His coat of arms featured three lions. He showed in essentially declaring war on his own father, throwing in his lot with brothers Henry and Geoffrey in disputing the king's planned division of land between his four sons. (The youngest was John.) Richard had a powerful supporter in his mother.

In 1173, when Richard was just 15, he found himself knighted by King Louis VII of France and at the head of an invasion force. The target was Normandy. The king's forces were victorious, and Richard ended the fighting by proclaiming once again to his father. He then turned around and stamped out a series of revolts by the barons of Aquitaine. King Henry II had crowned his oldest son, known as Young Henry, as king-in-waiting, and had demanded that his other sons pay homage to both. Richard refused and soon was the target of an attack by Young Henry and their brother Geoffrey. Richard defeated the combined force. In the next few years, Young Henry died, making Richard the heir to the throne. In 1188, Richard was again at odds with his famously irascible father; this time, Richard and John teamed up to oppose King Henry, their ally this time being the new French king, Philip II. As before Eleanor, by now well and truly estranged from her husband, supported the rebellion. The king's good fortunes had finally run out, and he surrendered, recognizing Richard as his sole heir. Henry died not long after, and Richard was crowned king at Westminster Abbey; this was on Sept. 3, 1189. Richard was ruler of the vast Angevin Empire, which Henry had built up through his time on the throne. Richard, feeling no need to keep up the pretense of ruling in his father's stead, chose to go on Crusade instead.

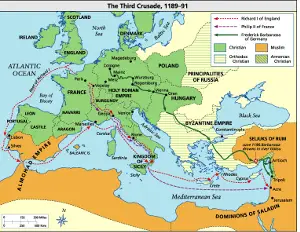

Pope Gregory VIII called the Third Crusade in 1189. Saladin, the Sultan of Egypt and Syria, had led the takeover of Jerusalem two years before, and Christian leaders in the West wanted to retake the city. Richard answered the call, as did Philip II of France and the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick I Barbarossa of Germany. Richard raided the royal treasury, gathered up a significant fighting force, and left for the Holy Land. He left behind a sizable army as well, overseen by regents Hugh, Bishop of Durham and William de Mandeville. The latter died not longer after this appointment; Chancellor William Longchamp then over as co-regent. Truly running the country was Arthur of Brittany, Geoffrey's son, whom Richard had named as his heir. John did not take kindly to this and started planning a revolt.

The Crusade nominally lasted three years; but, despite the presence of a large and well equipped Crusader army headed up by the three most powerful men in Western Europe, the Third Crusade ended in frustration, at least as far as its ultimate goal. Frederick Barbarossa drowned before the armies even got to the Holy Land, and most of the dismayed German forces left for home. Richard himself had some success. He and his men captured Messina, a city on the island of Sicily, in 1190; in the process, he rescued his sister Joan, who had been married to the King of Sicily and, when he died, had been taken captive by the new king. The following year, Richard's force took the island of Cyprus. Richard ruled the island for a time and got married, to Princess Berengaria of Navarre. Richard then sold the island to the Knights Templar. The English and French forces also seized the crucial city of Acre, in July 1191, Richard finishing off a siege begun by Guy of Lusignan, who then took over as King of Cyprus. One story of the struggle at Acre had Richard, debilitated from scurvy, being carried on a stretcher, wielding a crossbow to pick off guards on the walls.

Richard and his forces defeated Saladin's army at Arsuf in September and then took Jaffa in November. Richard's army was within storming distance of Jerusalem, twice, but the French force had left for home and he had lost too many men to take the city and ended up negotiating a treaty with Saladin. Richard headed for home. In 1192, the ship he was sailing on wrecked and Richard was forced to try to go home over land. He was captured and taken prisoner by Duke Leopold V of Austria, whom Richard had personally offended by defacing Leopold's personal flag at Acre. Henry VI, the new Holy Roman Emperor, had no such compunction to be an ally of Richard (as had his predecessor, Frederick Barbarossa) and, in fact, kept him captive, demanding a massive amount of money as ransom. Many sources say that the ransom was 150,000 marks, twice the annual income of the English Crown at the time and the equivalent of several million dollars in modern money. Richard had left Hubert Walter, the Bishop of Salisbury, in charge of running the country. He and Richard's mother raised most of the money but only by raiding the royal treasury and instituting a number of taxes. To pay the remainder, Richard had to hand over a number of nobles. While Richard was away, his surviving brother, John, tried to seize the throne. Hubert organized a successful defense force, and John had to end his usurpation bid. When Richard finally returned home, he forgave John but did not name him the heir to the throne. (Richard and his wife had had no children.)

Richard returned in 1193 but didn't stay in England for long. He spent much of 1194 on campaign in France, fighting to keep control of his lands in the face of attacks from Philip II of France. During one of these attacks, Richard sustained a wound that ultimately proved fatal. He was hit in the upper shoulder by a crossbow bolt. A surgeon who tried to remove the bolt made things worse, and the wound became infected. Richard lingered for a time and died on April 6, in his mother's arms. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White