The British Isles before Rome

Julius Caesar was the first Roman leader that we know about to bring a serious expeditionary force to the British Isles. He did this in 55 B.C. He didn't exactly get a warm welcome. The Latin name for the first inhabitants of what is now England was Britanni, after the Greek, translated as "Britannic peoples," from the travels and writings of a Greek geographer, Pytheas, in the 4th Century B.C. A later term that has been applied to these people is Celts or Celtic. When Caesar arrived, he found not a backwater but a burgeoning society, a collection of Celtic tribes, or clans, scattered across the land. Tribal leaders called themselves chiefs or kings and ruled from hill-forts defended by earthen banks and wooden walls. Chiefs or kings were supported by warriors or nobles, who had wealth enough to purchase armor and weapons and fine clothing. Hill-forts varied quite a bit in size. Some were nothing more than small structures designed to protect a small area. Other hill-forts were very large and very well-fortified. The center of Celtic life was the clan. Clans banded together to form tribes, in a sort of concentric societal structure. By and large, people lived in hamlets or villages and tended to farms or to village-centric vocations.

That heat inside the house came from a fire, which was also used for cooking. Also used for cooking were primitive ovens and hot stones. Low tables were used for eating and for storing things. Other furniture was scarce, and people routinely sat on the floor. They also slept on the floor, on mats or furs. In a prominent place would have been the loom, out of which fabrics were woven many months out of the year. A common treatment for the inside of a Celtic roundhouse was lime-washing the walls, to make it a little lighter inside. Interior lighting of any kind was not commonplace. Shared accommodations were not uncommon, and parents would often look after one another's children as they grew up.

Farms grew wheat, oats, barley, and rye. Farm animals most commonly kept were cattle and pigs. Farmers also had oxen, to pull iron plows. Horses pulled carts, and dogs herded livestock and hunted as well. The Roman historian-geographer Strabo talks of British hunting dogs being well-known in the Roman world. Travel was on foot or by horse, on unpaved roads, or in boats on the many rivers that dotted the landscape. Trade with the Continent was extensive, according to Strabo, with cattle and animal hides and gold and silver being traded from Britain for Continental ivory necklaces, amber jewelry, and glassware. In the Iron Age, gold and silver had replaced bronze as the metal of choice for coinage. Part 2: The Conflict |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

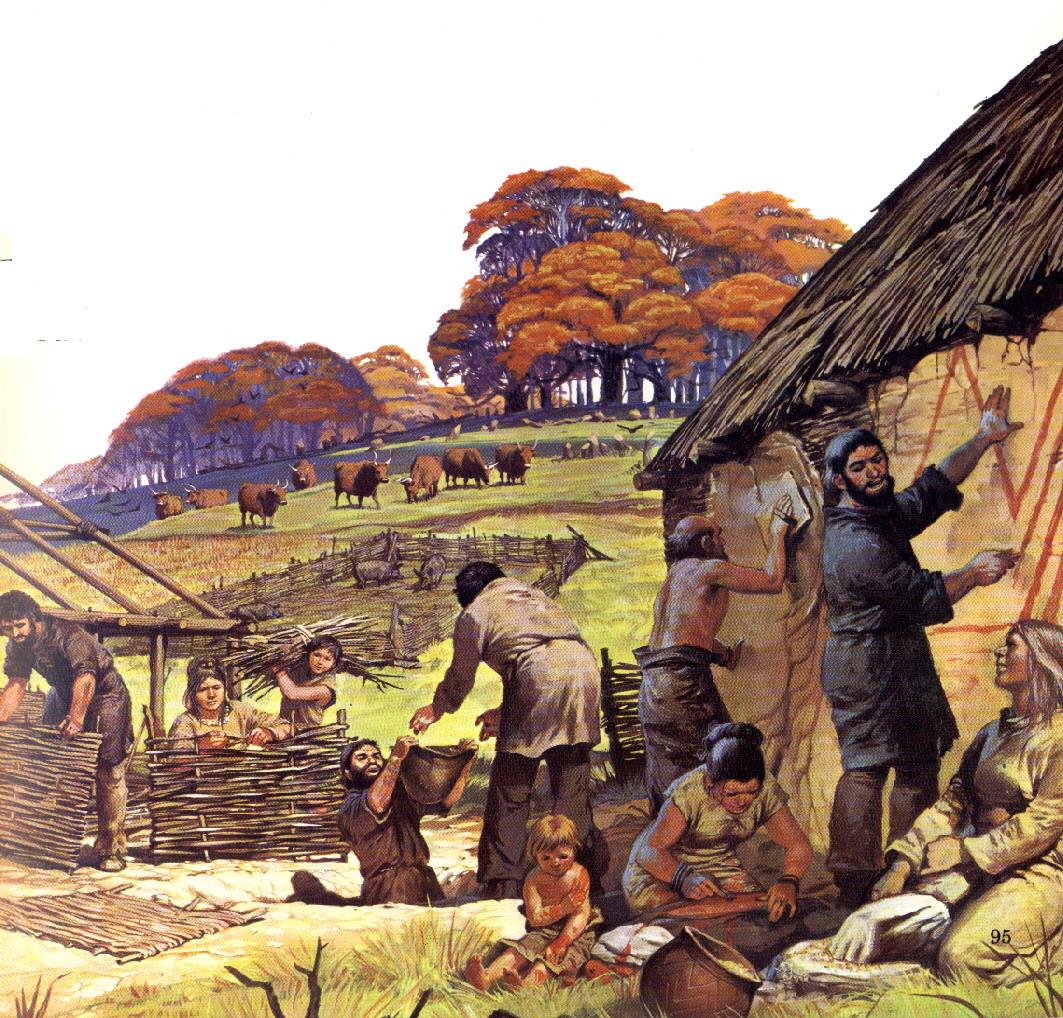

A common Celtic house was round, with a diameter anywhere from 5 to 15 meters, and had a thatched roof. Some sources say that there was a north-south division based on local available materials, so northern houses were made more of large stones held together with clay, whereas southern houses were made of wattle, or woven wood, and daub, a mixture of straw and mud. Either set of materials was constructed tight, to keep the weather out and the heat in.

A common Celtic house was round, with a diameter anywhere from 5 to 15 meters, and had a thatched roof. Some sources say that there was a north-south division based on local available materials, so northern houses were made more of large stones held together with clay, whereas southern houses were made of wattle, or woven wood, and daub, a mixture of straw and mud. Either set of materials was constructed tight, to keep the weather out and the heat in.  Outbuildings dotted the landscape, providing spaces for cooking and tanning and storage of food and supplies. Some outbuildings served to shelter animals as well. Surrounding these buildings were arable fields.

Outbuildings dotted the landscape, providing spaces for cooking and tanning and storage of food and supplies. Some outbuildings served to shelter animals as well. Surrounding these buildings were arable fields.