Gerrymandering: Congressional Redistricting for Political Gain

The legislatures of each individual state in the United States are responsible for drawing up maps that show the boundaries of individual voting districts in their state. Sessions to redraw such maps are done every decade, in the year following a U.S. Census. The first U.S. Census was done in 1790. Subsequent Census efforts have been completed in years ending in zero.

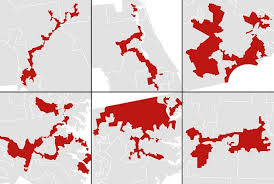

Sometimes, those in charge of redistricting will redraw boundaries of voting districts in an effort to influence the results of the next election. Records will show home addresses of voters who have registered a party affiliation. For example, a state legislature will likely know where all of the registered Democrats in a district live. In the same way, the legislature will likely know where all of the registered Republicans in a district live. Voters who have registered affiliation with other political parties will be captured in this way as well. Voters who have not declared an affiliation to any political party will be on a separate list. Redistricting efforts that cater to political advantage usually take two forms; in the vernacular, these are called "packing" and "cracking." The first strategy, commonly called "packing" is redrawing the boundaries of a district such that all voters registered with a particular political party affiliation are in the same district. On the assumption that all of those voters will vote for the candidate representing their political party, the result will be a victory for that party's candidate. The second strategy is more of a "divide and conquer" approach, by which the legislature redraws the boundaries of more than one district to, in effect, split the influence of a political party. As an example, if the legislature finds that 1,000 members of a certain political party live in a particular district, the legislature, if it wants to blunt the political power of those 1,000 people, might redraw the boundaries of a few districts so that those 1,000 people no longer live in the same district but, rather, live in multiple districts. The political influence of 1,000 people affiliated with one political party would then be split among multiple districts. Taken to an extreme political advantage, the legislative majority belonging to one political party would redraw district boundaries to favor candidates belonging to the majority party and "disfavor" candidates belonging to other parties, primarily the other large political party. For example, if the Democratic Party had a majority in a state legislature and was in charge of redrawing the district boundary maps and embarked on a strategy of "packing" that put all of the Republican voters into one district, this might effectively ensure that the election in that district resulted in victory for the Republican candidate but that the elections in other nearby districts did not result in victory for the Republican candidate, on the theory that voters would vote for the candidate of the party which they themselves were affiliated. Since the vast majority of members of state legislatures are either Democrats or Republicans, this "packing" scenario would result in a victory for Democratic candidates in multiple districts. In the same way, if the Republican Party had a majority in a state legislature and was in charge of redrawing the district boundary maps and embarked on a strategy of "cracking" that put all of the Democratic voters in one district into five different districts, then that, in theory, would increase the chances of victory for the Republican candidates in those five districts, especially in the district that previously had a large number of Democratic voters. Since the political party doing the redistricting is likely to use these strategies to its benefit, the likely result is the re-election of incumbents belonging to that political party. No American laws prohibit this practice. In fact, it is not a new phenomenon. In the same way that these strategies are commonly called "packing" and "cracking," the overall strategy of redrawing district boundaries is referred to as "gerrymandering." The term comes from the early days of the United States, specifically from the Election of 1812. The word "gerrymander" was first used in the Boston Gazette on March 26, 1812. The newspaper published a map showing the redrawing of the Massachusetts state senate election districts. Overseeing the redistricting efforts was Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry. The map published in the Gazette was of the Essex County district, and it was a very unusual shape indeed. The newspaper turned the map into a cartoon that depicted the map as a dragon-like monster, like a salamander. The cartoon monster had claws, wings, and huge teeth. The newspaper also included a supposed history of the creature. Combining the last name of the governor, Gerry, with the word salamander, the newspaper came up with the word "gerrymander."

Regardless of what it was called, the strategy proved effective for Gerry's political party, the Democratic-Republican Party because Essex County's was not the only district whose boundaries had been redrawn. The popular vote in the Election of 1812 was divided roughly evenly between the two major parties, the Democratic-Republicans and the Federalists, yet the Democratic-Republicans won 29 of the 40 seats in the senate that year. The term proved quite popular as has been used to describe the practice ever since. It was first published in a dictionary in 1848 and first published in an encyclopedia in 1868. The one thing that has changed in the years since the introduction of the term is the pronunciation. Elbridge Gerry pronounced his last name with a hard G, like the name Gary. The current pronunciation of the word sounds more like the name Jerry. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

Most state legislatures will have a majority belonging to one political party (and this is currently, in all cases, either the Democratic Party or the Republican Party). In practice, that means that the business of government in that legislature is usually run by the party holding the majority. Committee chairs commonly belong to the majority party, session agendas are set by the party's majority leader, and special projects like redistricting are run by the majority party.

Most state legislatures will have a majority belonging to one political party (and this is currently, in all cases, either the Democratic Party or the Republican Party). In practice, that means that the business of government in that legislature is usually run by the party holding the majority. Committee chairs commonly belong to the majority party, session agendas are set by the party's majority leader, and special projects like redistricting are run by the majority party.